Muziris has a magical ring to it and is one of the few names that sound better to me in English than in Malayalam. It is somehow mystical and its relevance in Kerala history beckons one to make a visit. So, off I went last week to have a look at the Muziris Project. Ideally, I think one should spend two days here, taking in the sights at leisure but I had to fit everything in one day.

Cheraman Perumal, the then King of Kerala (Bhaskara Ravi Varma says Wikipedia), travelled to Saudi Arabia in the seventh century along with some Arab traders and met Prophet Mohammed. He then converted to Islam and died at Oman on his way back to Kerala. He had sent some letters through the Arab traders who were travelling with him, instructing the authorities to whom he had handed over his kingdom when he left for Arabia, to provide all help to the traders. Malik Dinar, who was one of the traders sought help to build a mosque and that is how the Cheraman Juma Masjid came to be. This was built in AD 643 (the date is contested though) at Kodungalloor and thus, is the oldest mosque in India. The mosque had undergone several reconstructions, which damaged the original structure built in traditional Kerala style. I was told that one of the reconstructions made it into a hideous structure like the new concrete mosques that we see everywhere. Thankfully, when the Muziris Heritage Project was launched by Kerala Tourism, they understood this aspect and have now restored the mosque to its original design. This work has been going on for many years and is still not finished. Without a doubt, it is the most beautiful mosque that I have seen in India.

Inside the mosque, you can see the graves of Habib Ibn Malik and his wife. He was the nephew of Malik Dinar and took over the mosque from Malik Dinar. The mosque is quite small and there are carpets on the floor for devotees to pray. Photography is not allowed inside the mosque.

The building is very beautiful and very well proportioned. There is a pond behind the mosque for ablutions. The authorities are now digging under the structure of the mosque to make more space for devotees.

Next stop was the Kottappuram market and the fort. There is a nice walkway along the banks of the Periyar river, where the market ends. Just next to the market is a beautiful square. This must have been where all goods were unloaded after being brought on boats through the river and then distributed. All this has now been developed as part of the Muziris Project. You can still see some old buildings in the market.

The Kottappuram Fort is quite near to the market but there is nothing much to see there. It was built in 1523 by the Portuguese and then it changed hands going through the Dutch, Hyder Ali and the Travancore kings. You can just see a couple of walls and there is no information whatsoever to explain the significance.

My first memory of the word Kodungalloor would perhaps have been associated with Bharani. It is in my list – to be at the temple on the day of the Bharani festival. Since I was at Muziris, I wanted to see the temple. It stands on a reasonably large plot of land and with enough trees that have resting places built around them. It was very calm and peaceful when I visited and I tried to imagine how it would be on the Bharani day with all the mass hysteria and the women all in a frenzy; it would be quite a sight.

I clicked a couple of photos and then someone told me that you need special permission to take photos inside the temple compound.

Paravur is just a few kilometres from Kodungalloor and is the seat of the famed Paliam family. They were the ministers of the King of Kochi and thus, had amassed huge wealth. They own a lot of property in Paravur and it seems the partition deed of their family, executed in 1956, is one of the biggest partition deeds in India. As part of the partition, two buildings have been brought under a Trust and is open for the public as museums. One is the palace that the male head of the family, called Paliath Achan (the minister) lived in, and the other is a traditional Naalukettu that the ladies of the family lived in. The buildings are maintained very well with detailed explanations provided for visitors. The Muziris Project has also appointed guides who take you around the buildings and they explained in detail about the history, the houses etc. The palace was built by the Dutch in gratitude for the help that Paliath Achan extended to them to beat the Portuguese. Hence the construction has significant European influences like very thick walls. The buildings themselves were more functional than ornamental. Unfortunately, no photography was allowed inside the buildings; I don’t understand why they don’t allow photography in such places, a pity indeed.

Next was the visit to synagogues. Muziris had a significant Jewish population and in this vicinity itself there are three synagogues even now – Paravur, Chendamangalam and Maala. The Paravur Synagogue is one of the oldest synagogues in India and it is believed to have been built in 1105 AD by Malabar Jews. They were the earliest Jewish settlers in India, and it is rumoured that they were sailors from King Solomon’s period. However, the earliest that Jewish settlors can be traced back to, as per records, is 70 CE. So, they have been in Muziris area for more than 2000 years with the last Jew emigrating to Israel a few years back. The next set of Jews arrived in the 17th century from Iberia, and they were called Paradesi (foreign) Jews and the synagogue they set up in Kochi is called Paradesi Synagogue. The Paravur Synagogue was torn down by the Portuguese and then reconstructed in 1616 AD. This is the largest synagogue complex in India and the influence of Kerala architecture is quite visible. You enter the complex through a two-storied gate with some rooms (padippura), the upper floor of which is connected through a covered walkway (over a courtyard) to the main part of the synagogue. Women entered through this part and were separated from men as they stayed in an upstairs gallery. This was news to me as I have not seen this separation in any other synagogue. Later, I saw the same architecture in Chendamangalam Synagogue as well.

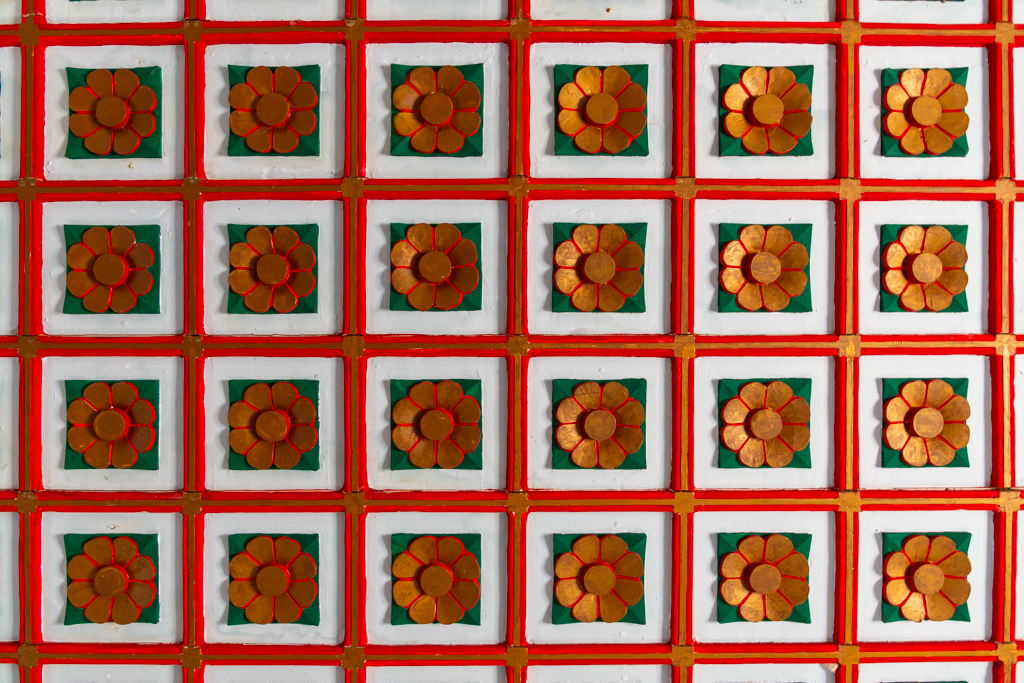

The main area consists of a hall where there is a raised wooden platform called the Bemah or Tevah. This is a structure in the middle of the room, and it faces the Ark, which is a wooden structure along the wall that is closest to Jerusalem. The books of Torah were stored inside the Ark. The original Ark (from 1100 AD) used to be there at this synagogue, and it has since been removed and taken to a museum in Israel. A replacement Ark is in place now. The ceiling is from 1616 and is still surviving. It looks very solid with nice workmanship. The synagogue is not used for worship and the last service was conducted in 1958. Jews from Kerala left in large numbers after 1950, after the formation of the state of Israel and it seems that for prayers to take part in a synagogue at least 10 male members should be available and since the numbers dropped because of the migration, the synagogue ceased to be in active service.

There was a group of American Jews visiting the synagogue the same time as us and they started singing some hymns. That was quite a nice experience – to listen to those songs in a temple that must have reverberated with such worship centuries ago. Muziris Project has provided guides here as well and they were also quite impressed by the singing. I asked the Americans about the separation between men and women in the synagogue and they said it was a practice followed by conservative Jews.

Much to my irritation, photography was banned within the Paravur Synagogue as well and I had to be satisfied with a photo of the building from outside.

Chendamangalam Synagogue proved to be an exception to the silly “no photography” rule, and I was very thankful for that. This one also had a padippura though it was connected directly to the main room of the synagogue as there was no courtyard. The Ark, Bemah, ceiling and the upstairs gallery were all well maintained. This was also constructed by the Malabar Jews in 1420 AD. There were a few tombstones displayed in the yard of the synagogue. These tombstones were taken from the nearby Jewish Cemetery.

Muziris Heritage Project is a prestigious project of the Kerala Government to promote tourism and to protect our heritage. They have done a commendable job in maintaining many of these sites and providing guides everywhere as mentioned above. The guides themselves were quite enthusiastic and ready to help and explain. There was also some amount of information displayed in the Paliam houses and the synagogues. Unfortunately, not enough attention is being given to marketing or publicising information about these places. A guide at one of the synagogues told us that even during peak season they get only about 50 visitors in a day. This is because an average tourist doesn’t even get to hear of this. For instance, when I searched in Google for “Sights to see in Kochi” Muziris didn’t come up at all in the list of 30 provided by the first two listings – TripAdvisor and Thrillophilia. It is a shame that a location with such potential is being wasted like this. Any one of the four buildings – the two Paliam houses or the synagogues – is by itself enough to attract a good number of visitors. In addition are the possibilities of beautiful inland waterways. Government has bought a few boats, and these are slowly rotting away as they are not used at all. At the Kottappuram Fort, there is an office structure that has enough space for an Information Centre, but nothing is available there. A very sad situation indeed.

As I drove back from Muziris, I was a bit sad as I reflected on the current situation in India. Muziris is a showcase of how we lived in harmony between all religions. Within stone’s throw, you have a very old temple, mosque, church, and synagogue. There was a lot of give and take between the religions and the people and subsequently, in their customs. For example, it seems that the Malabar Jews used “thali” when they got married. They even had prayers in Malayalam. From that period of co-existence, we have come to a situation of separation of minds and people and even possible ghettoisation. Very sad.