Floating Monasteries! What image does that phrase bring up, when you close your eyes? I actually pictured medieval buildings floating in air. Needless to say, this caught my fancy, and I decided to include it as part of our itinerary during our visit to Greece. I am talking about Meteora, which literally means “suspended in the air” in Greek; the land where twenty four monasteries were built on inaccessible peaks. Monks started settling in this region of Thessaly from the 11th century itself; some records says that monks with climbing skills had been living in rock caves since the 9th century. In the 14th and 15th centuries, these Christian monks faced increasing persecution as the Ottoman empire expanded and, in this period, these monasteries were built on inaccessible locations so that the monks would have a safe haven. How they managed to build in such places, is quite beyond me.

The town nearest to Meteora is Kalabaka, which is about three and a half hours’ drive from Athens. Kalabaka is basically a small, quaint one street town with some nice restaurants. There are day trips by bus from Athens but since we prefer to explore on our own and wanted more flexibility, we decided to rent a car and drive. We started from Athens by mid-morning and arrived at Kalabaka by around 3 pm. While there were twenty four monasteries that were set up during the medieval period, only six are operational now and they house about 17 monks and 40 nuns. The monasteries are all set up to handle the tourist traffic and you don’t see any monks or get to see the areas that they use regularly. These monasteries are closed on different days of the week and our plan was to spend the afternoon of Sunday and full day Monday at Meteora and cover the important monasteries, as all but one of the monasteries were open on those days. An additional point to be considered while planning the itinerary is that the monasteries close by 3 pm or 4 pm. On the day of arrival, we had planned to go to the Holy Trinity Monastery and so we rushed there, soon after check in.

This monastery is also known as Agia Triada and is a difficult to access as it involves climbing up some 140 steps. It was set up in 1475-76 according to Wiki though local legend says that the monk, Dometius, the founder of the monastery, arrived at the site in 1438. During the initial times, it could only be accessed by ropes. This was the case with most monasteries, and it was only about 90 years back or so that the Greek government made roads that could help with the access to these monasteries.

We made the climb up the 140 steps without too much trouble and there is a small courtyard on top and a chapel. The views were just breath taking and I don’t think I am capable of describing it. On the top, we found the arrangement used by monks in earlier times to haul up people and material. There is a large pulley like attached to a rope that passes over a hook dangling over a sheer drop, right to the bottom. People and material were then carried up in a rope net; the steps we used were added much later. Of course, prior to this arrangement, access was possible only through rope ladders and whenever the monks faced any threat, they simply pulled up the rope ladders and secured themselves. Some of these rocks are about 400 metres high and going up and down must have taken some effort! These days, there is also a small cable car type of arrangement from the car park directly to the monastery. This is used for transporting goods and the monks that can’t make the climb.

The Monastery of Holy Trinity was featured in the 1981 James Bond film “For your eyes only” and couple of other films as well.

You can see many unusual and thus interesting rock formations as you drive around the mountains in Meteora. Wiki says that about 60 million years ago, a series of earth movements caused the seabed to go up, creating a high plateau. The rocks are mostly sandstone. There are many trails one can take in Meteora but we didn’t try any because of lack of time. There are many rocks that can be accessed from the road, or the car parks and climbers would really love it.

As can be expected, such a location has great sites to watch the sunset and there is enough information to be found on where to go, on the internet. After finishing the Holy Trinity Monastery, we went to Sunset Rock and the sunset was just amazing. It was so peaceful and quiet. No wonder that the monks came to this area, meditation comes rather naturally here. We made best use of our two evenings at Meteora and visited two spots and spent time there. There was a reasonable crowd in each location, and you had to arrive a bit early to get the best spots.

One interesting aspect I noticed is that there is no railing or any such protection anywhere. You are expected to behave reasonably and sensibly and watch out for your own safety. The drops are rather sheer and deep and a fall could definitely be fatal. On the second day evening, someone lost a bottle or something like that and it caused a little bit of consternation among those present – guess it struck everyone that it could be you instead of the bottle, if you aren’t careful!

Next day morning, we set out to see the most famous of the Meteora monasteries – The Great Meteoron. It is the oldest and largest of the monasteries and was founded in 1356. We arrived early, as soon as the monastery was opening up, as this place could get crowded as the buses from Athens started arriving. Even then, we had to wait for a bit. This is quite a steep climb (more than 300 steps) and we overheard a Malayali family discussing the climb and in the end, the elderly parents decided to not attempt it. This monastery also has a cable car from the car park area, but I guess it is only for official use. We made it to the top without any trouble and the climb itself is worth it because of the views, especially that of the Monastery of Varlaam, which is quite nearby.

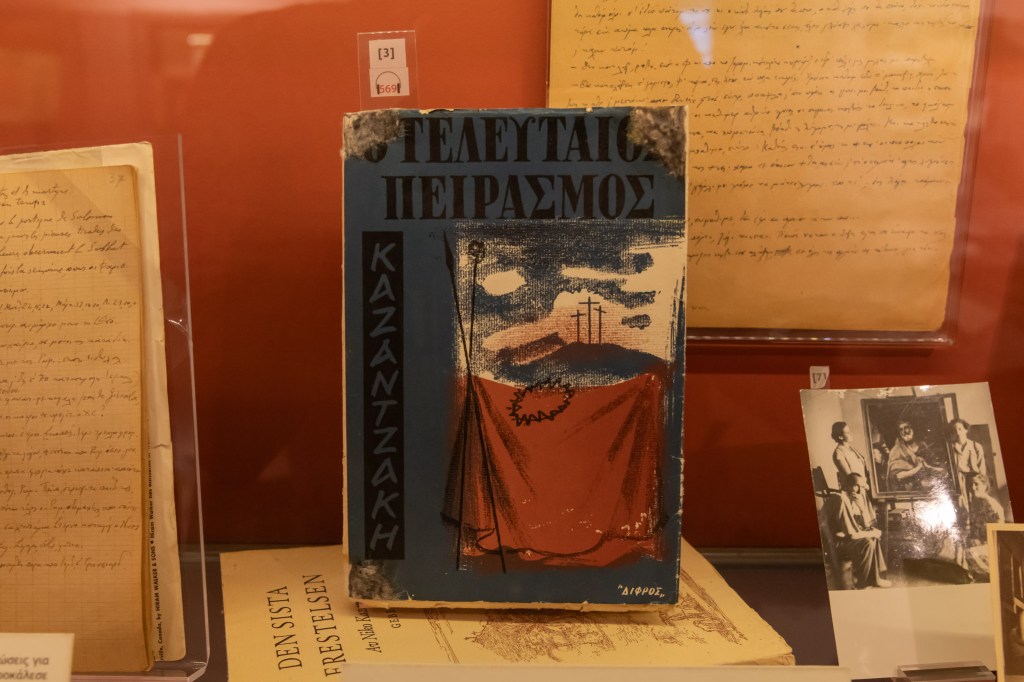

There are many buildings at the top including a beautiful church, courtyard, kitchen etc. Some of the areas have restricted access and there is no photography allowed inside the church (the image below is one I found on the internet), which is quite a pity as the interior of the church is quite rich and beautiful. There is also a museum inside the monastery and supposedly, the library at the Grand Meteoron is the largest in Meteora and it has about 1350 codices.

The courtyard had some beautiful frescoes and the rope net arrangement was seen here as well.

View of Monastery of Varlaam from the Great Meteoron.

The kitchen was pretty large and had all kinds of utensils, baskets and all preserved as it might have been in the olden times.

The Great Meteoron left us in awe, and we all felt it was well worth the effort. It was quite hot in Meteora in June and the sun was doing its best to make it even more uncomfortable. Next on the list was The Monastery of Varlaam. It is the second largest monastery in Meteora and was founded in the mid of the 14th century by a monk named Varlaam. After Varlaam died, the rest of the monks deserted the monastery, and it was abandoned for a century of so till two monk brothers named Theophanes and Nectarios reactivated it.

This is a beautiful monastery, and you have to go up some 200 steps or so before you step into a wonderful courtyard.

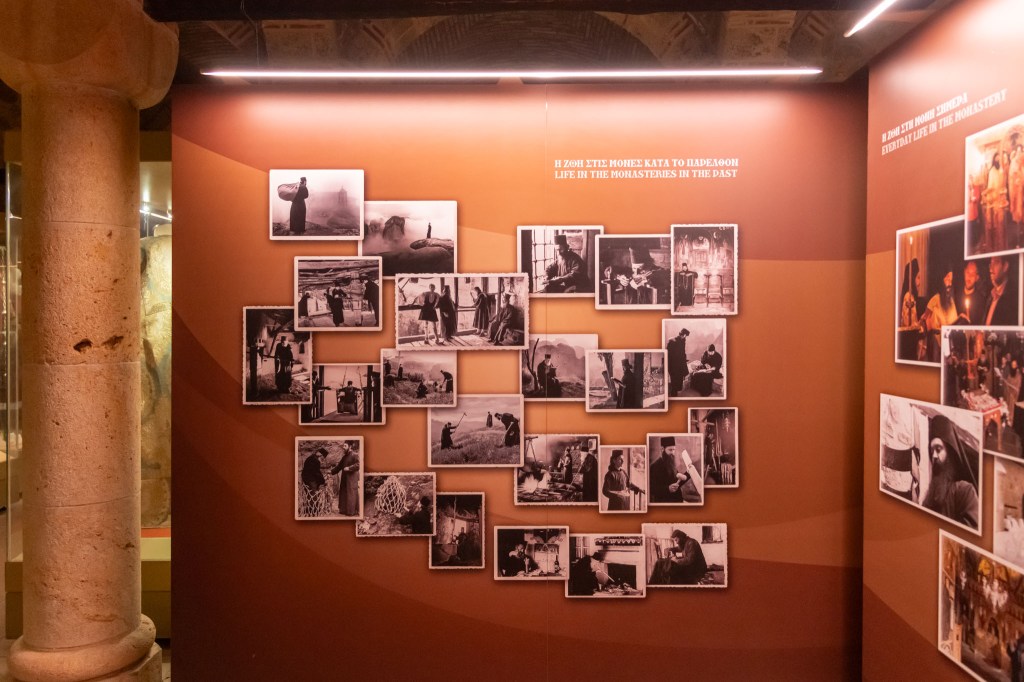

There is a small museum that brings out how life was, for the monks in the olden times. I found that quite interesting. I tried to imagine myself as a monk here, without the tourists milling around, contemplating the mysteries of the universe and time. If there is a ranking of locations suited for such an activity, this must definitely be one of the top-ranking ones.

There is also a small room with beautiful frescoes and a fantastic ceiling.

Here too, photography is banned inside the church – which is quite a pity – and I reproduce an image I found from the internet.

One key attraction at the Varlaam is a wooden barrel that was used to store rainwater. This is a huge barrel which can hold up to 12,000 litres. It is made entirely of wood and the locking system to make the planks watertight is quite clever.

The lift arrangement used in other monasteries was found here as well.

After lunch, we proceeded to the Monastery of St. Barbara or Roussanou. This is a small monastery, occupying the whole of the rock it stands on and was built in the 14th century. These days it is occupied by nuns and about 15 nuns live here. It is very easily accessible from the road and from the other side, there is a wooded path that leads to a bend further up the road. The Malayali family we had seen at The Great Meteoron came here as well and a nun came out to meet them. So, I assume a Malayali nun has made it to this remote monastery. We didn’t see them afterwards and so couldn’t check the veracity of this assumption.

Photography wasn’t allowed inside the monastery, but I wasn’t aware of this and clicked a few photos before the clerk alerted me.

It has a nice small chapel and some displays in a room outside. The pathway through the woods, behind the monastery, is quite enjoyable.

This was the fourth monastery we visited, and we didn’t have enough time left, to visit the remaining two. The two days involved a lot of going up and down steps and we were happy we could handle it without any trouble.

Meteora is a magical place indeed and I wasn’t disappointed that the experience didn’t do justice to the image that came into my mind when I heard of this place the first time. The town of Kalabaka is pretty nice too and I can easily see myself spending a week here trekking to the various monasteries and taking life easy, in between. It was our last evening at Meteora and we soaked in one more sunset before we said goodbye.